The war after the war

U.S. Grant and the mostly forgotten tragedy of Reconstruction

By Rick Holmes

GateHouse Media

Americans talk a lot about the Civil War, but not nearly enough about what happened in the years after. In history class, it’s “the Union won, Lincoln was shot, now let’s talk about the westward expansion.”

Missing from these lessons is war after the war, a battle for racial equality that had to be fought again a century later and that still divides us. We call that American tragedy Reconstruction.

With the end of the war in sight, Abraham Lincoln promised to bind the nation back together “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” What a stirring call. What an impossible task.

White southerners had been defeated, not converted; the Old Guard was intent on re-subjugating freed slaves. To the freed slaves and their Republican allies, emancipation wasn’t enough. They wanted education, economic opportunities and civil rights.

Delivering on Lincoln’s promises fell, more than anyone else, to U.S. Grant. Ron Chernow’s recent biography of Grant – not exactly a beach book, but a worthy summer read – puts the famous general in a new light: that of a key figure in America’s long struggle for racial justice.

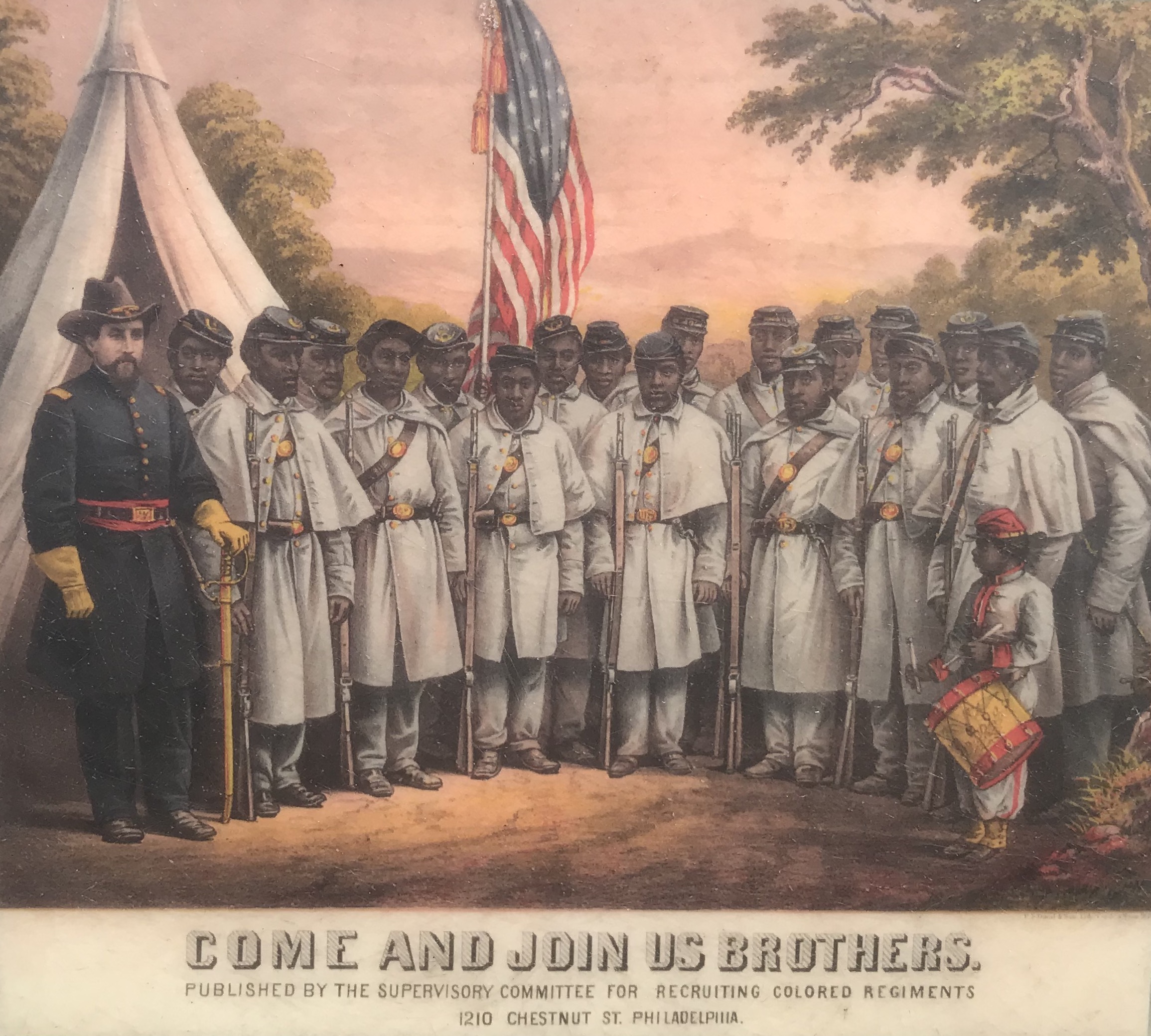

More than other generals, Grant embraced Lincoln’s thinking on race. He dealt generously with the ex-slaves that arrived in droves at his encampments as his army reconquered the South. He put them to work, as paid labor and as soldiers. He organized some of the first “colored” regiments and sent them into battle, where they proved capable and courageous.

As general, Grant sent federal troops into southern cities to put down white violence against blacks and protect voting rights, even as the president – Andrew Johnson, who was vice-president when Lincoln was assassinated – did everything he could to restore the power of the Confederate aristocracy.

Chernow describes Johnson was a proud racist, adamantly opposed to letting African Americans vote or hold public office. He was also a bad politician, managing to alienate just about anyone within earshot. As soon as voters had the chance, they sent Gen. Grant to the White House.

As president, Grant was a champion for black advancement. He invited black leaders into the White House. He appointed blacks to his administration and named the first black ambassadors. He made abolition of global slavery a diplomatic priority.

Grant pushed for the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed the right to vote for all citizens, and he enforced it where he had the authority. With millions of black voters enfranchised, Republicans won elections to local offices across the South. Two black senators and 15 black representatives were sent to Congress.

It was an exciting time for African-Americans. The Freedmen’s Bureau provided jobs and assistance for newly freed slaves. Northern philanthropists founded schools and universities. Schools and streetcars were being integrated, in the North as well as the South.

But there was resistance, especially in the South.

A lot of Confederate soldiers traded in their gray uniforms for the white robes of the Ku Klux Klan, often taking orders from the same officers they followed on the battlefield. This time they went after civilians, not Union soldiers. They drove Republicans – white and black – from their homes, destroying their businesses and taking their lives.

Congress created the Justice Department and gave Grant new powers to put down the Ku Klux Klan, but other groups took its place. “Redshirts” and “White Leagues” organized armed coups, driving elected Republicans from their offices. White mobs murdered blacks by the dozens in Memphis, Vicksburg and New Orleans.

The worst of the massacres came on Easter Sunday, 1872, in Colfax, Louisiana, when at least 150 black men defending an elected parish government were murdered, their bodies thrown in the river or left to rot. Almost none of the perpetrators of the violence were prosecuted by the white supremacists who had returned to power in county seats and state capitals. A few responsible for the Colfax massacre faced federal charges, but they were overturned by the Supreme Court.

Eventually, voters up north grew tired of interventions into southern quarrels. Congress passed, and Grant signed, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed segregation in public accommodations. But it was never enforced and was eventually declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Elections – and Supreme Court appointments – have consequences.

History doesn’t dwell on unhappy endings. Reconstruction failed, replaced in the South by the Jim Crow era of racial oppression. School history lessons adopted the Lost Cause explanation that Radical Republicans had tried to go too far, too fast, and that freed slaves weren’t ready for real freedom.

We ought to be teaching new lessons about that ugly era, about how the ideals that fueled America’s most deadly war were dashed by a white supremacist counter-revolution. We ought to celebrate the forgotten martyrs and heroes of the first civil rights movement, starting, perhaps, with U.S. Grant.

Inspired by an earlier Chernow biography, Lin-Manuel Miranda turned Alexander Hamilton into a revolutionary rock star. Maybe it’s time he brought Grant to Broadway.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.