Woodstock and the Class of ‘69

By Rick Holmes

July 19, 2019

Bethel, NY – Fifty years later, the cow pasture where an out-of-control rock concert once grabbed the nation’s attention is still mostly a cow pasture in the middle of nowhere.

There’s a convenience store on the road to what used to be Max Yasgur’s farm, decorated with tie-dye and peace signs. There’s a small museum and a performance venue that preserves the legacy of the weekend when more than 400,000 young people flocked on a makeshift festival site that couldn’t have handled a crowd half that size.

Early on, the promoters gave up on taking tickets and declared Woodstock a free concert, which only brought more people. There was an epic traffic jam. Food was scarce, sanitation was horrible and then the rains came. The TV news showed dirty hippies as far as the eyes could see, partying proudly with drugs, sex and some terrific rock ‘n’ roll.

In the summer of ’69, Americans were already divided over politics, hairstyles and premarital sex. Woodstock divided them again, between those who were aghast that such a thing could have happened and those who wished they had been there.

I fell into the latter category. If memory serves, a friend and I stood for more than an hour on a highway entry ramp with our thumbs out – hitchhiking was an accepted way to get around way back then – but couldn’t catch a ride and gave up.

I had just graduated from high school and, like most of us in the Class of ’69, I was hungry for adventures and meaning, movements and a good time. I didn’t make it to Woodstock, but I was there in spirit.

Looking back, that was quite a summer for America.

In June, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio, one of the most polluted rivers in the country, caught fire. It wasn’t the first time the oil slick floating on the river had ignited, but this time it became a symbol of America’s degraded environment. It helped inspire passage of the Clean Water Act and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

On June 28, the Stonewall riots erupted in New York’s Greenwich Village, helping launch the gay rights movement.

Three weeks later, Sen. Ted Kennedy drove his car off a little bridge and into a pond in a little-known place called Chappaquiddick. Kennedy survived, but his passenger, 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne, drowned. The accident effectively killed the presidential hopes of the surviving Kennedy brother.

Then another shock, as police discovered the gruesome scene of a mass murder in Los Angeles perpetrated by the cult followers of a wannabe rock star named Charles Manson. Five people were killed, including actress Sharon Tate, then eight months pregnant, in an act Manson had hoped would ignite a race war.

But all was not grim. In July, the first man walked on the moon, and America was transfixed. The national goal set by John F. Kennedy had been attained. We beat the Soviets. U.S.A! U.S.A!

But to a lot of us in the Class of ’69, the moon landing was a fleeting thrill. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were dead, Richard Nixon was president and young Americans were growing more cynical by the day.

Our concerns were more immediate. Every male member of the Class of ’69 carried a draft card in his wallet featuring a status code. If you were enrolled in college, or had a friendly doctor who could certify you had bone spurs or some other debilitating condition, the code said you could go about your business. If you had no deferment, you were classified 1A, meaning at any time you could be sent off to Vietnam, where nearly half a million Americans were fighting and dying in a deeply unpopular war.

America was winning in space and losing in Vietnam. Its leaders were discredited or dead. We had mass murder in the Hollywood hills and the rivers were burning. No wonder the Class of ’69 was confused, angry and dreaming of getting “back to the garden.”

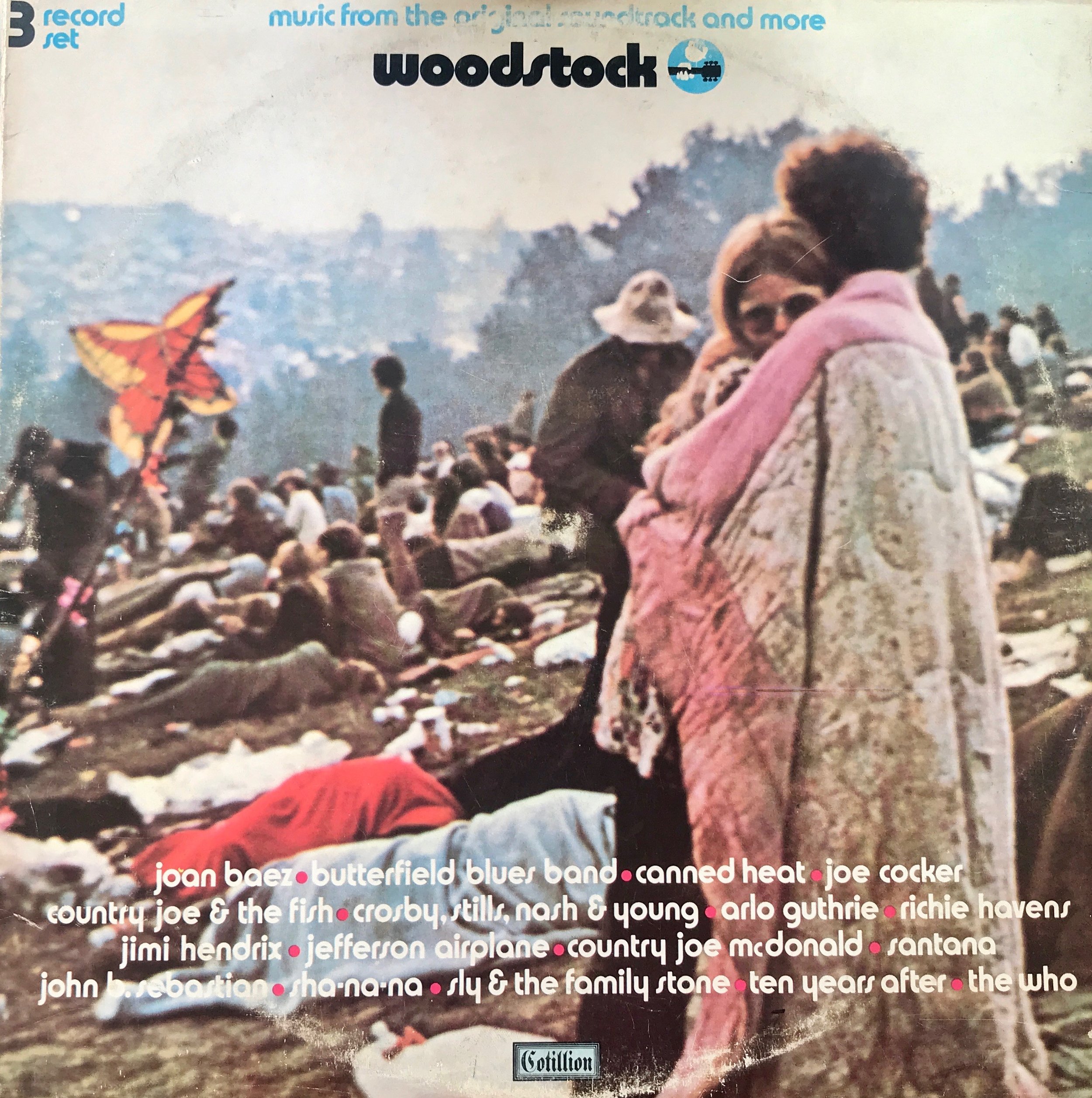

Then came Woodstock. It was a logistical mess, but there had been no violence and no strife in what, for a weekend, had become the second most populous city in New York. National media turned it into a positive narrative, soon reinforced in song, a movie and a three-disc album now gathering dust in an attic near you. The “peace and love” crowd had lived up to its ideals and was given a new name: the Woodstock Generation.

It was mostly bunk, of course, as generalizations about generations usually are. Baby Boomers were a diverse group and the audience at Woodstock wasn’t all that representative. But the media had been fixated on the Boomers for years, mostly because the children of America’s thriving post-WWII middle class had more money to spend than had any previous cohort of teenagers.

Boomers had been reading their own press releases since they’d learned to read. All our lives we’d been told we were special. When the rock stars and the national newsmagazines told us we could change the world, we wanted to believe.

In time, we learned better. Now all that’s left is the music.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, and follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.