Removing the Indians

By Rick Holmes

Jan. 18, 2019

Daviston, Ala. – Battlefields tend to be quiet places, but the Horseshoe Bend National Military Park was really dead the day I visited. The federal government was partially shut down over President Trump’s wall, so Horseshoe Bend, like other sites managed by the National Park Service, was closed. What locking Americans out of historical sites has to do with border security is beyond me.

I snuck under the gate and looked around anyway.

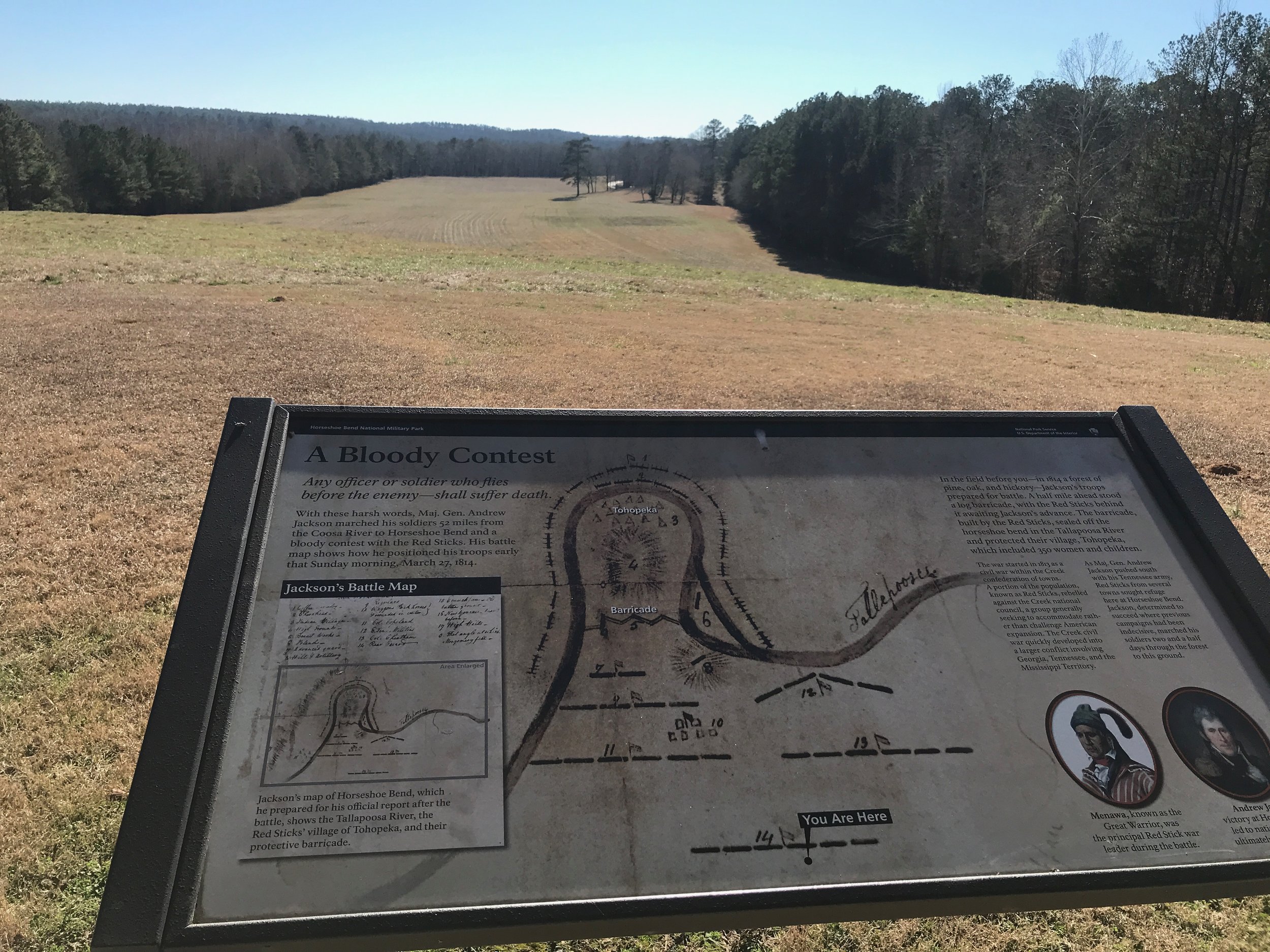

On this spot, on March 27, 1814, forces under the command of Andrew Jackson crushed the faction of the Creek Indian tribe that had been fighting back against the white incursions on their land.

Things were unsettled and complicated here in the Southeast at the beginning of the 19th century. Florida belonged to Spain in theory, but that was disputed in practice by Seminole Indians and settlers from the U.S., with Britain agitating the situation. Settlers were moving inland from the coastal states, taking over Indian territory. As in previous wars, Indian tribes allied themselves with European and American nations according to their perceived interests.

The Creeks, whose territory once included most of what is now Georgia and Alabama, had made peace with the Americans. The first treaty George Washington signed as president was with the Creek Nation, promising they could keep their lands and that the government would not protect settlers on Native soil. Washington gave tribal leaders a medal, along with plows and domestic animals “that they may be led to a greater degree of civilization.” The medal lasted far longer than the promises.

Twenty years later, the Creeks, a loose confederation of Muskogee-speaking bands, were split. One faction, led by members who had prospered from trade with the Anglos, was willing to accommodate the rising tide of settlers. This group, known as the Lower Creek, dominated the Creek National Council, which agreed to the construction of the Federal Road through the heart of their territory.

The other faction was called the Upper Creek or Red Sticks, after their painted war clubs. They resisted assimilation, sought to revive cultural traditions and opposed the Federal Road. Inspired in part by a visit from the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, the Red Sticks went to war against their Lower Creek rivals and some of the settlers on tribal lands.

Jackson, then an officer in the Tennessee militia, never paid much attention to treaties. When the settlers called, he crossed over into Alabama and went after the Red Sticks. With help from Indian allies – mostly Cherokee and Lower Creeks – Jackson chased the Red Sticks from battle to battle.

Jackson caught up with the last of the Red Sticks barricaded in a village at this horseshoe-shaped bend in the Tallapoosa River. Jackson lined up some of his forces across the river from the village, and attacked from the top of a hill overlooking it. His cannons proved ineffective against the fortifications the Red Sticks had erected, so Jackson ordered a bayonet charge.

It was a bloodbath. After it was over, the Americans took a nose-count to tally the casualties, cutting off the noses of the dead Indians so they wouldn’t be counted twice. Their count showed 857 Red Stick Creeks killed, compared to 70 deaths among the Americans and their Indian allies. Jackson took 350 Creek women and children prisoner.

That was it for the Red Sticks, and for the Creeks who had fought alongside Jackson. At a treaty conference, Jackson forced the Creek leaders to cede more than 21 million acres – most of today’s Alabama – to the southern states. To the Creek leaders stunned by his harsh terms, Jackson explained that “we bleed our enemies in such cases to give them their senses.”

Jackson’s victory in the Creek War, along with his victory over the British in the battle of New Orleans, made him a national hero and eventually led him to the White House.

But Jackson wasn’t done with the Indians. A few years later he found a pretext to invade Spanish Florida, raiding communities of Seminoles and escaped African slaves, then annexing Pensacola. And once he got to the White House, he signed the Indian Removal Act, which forced the Creeks, Cherokee, Seminoles, Choctaws, and other tribes to leave everything they knew behind and move to Oklahoma, often at gunpoint.

Thousands died before getting to their new home Uncle Sam had exiled them to. The Indians called the route they took the Trail of Tears. Today, historical markers line that terrible road, but there’s no sign of Indians.

One remnant, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, survives in Alabama. They have about 2,300 members, a small reservation, and operate three casinos. Other than that, the Indians have been removed, out of sight and mostly out of the nation’s mind, but that’s another story. What’s left are a few battlefields as silent and empty as Horseshoe Bend.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.