Malaga Island and Africatown

Untold stories of lost communities

By Rick Holmes

Aug. 4, 2017

They are two communities half a continent apart, lost and mostly forgotten, their stories rarely told. Both provide windows into our nation’s past.

The first is Africatown, the final destination of the last shipment of the American slave trade.

Importing African slaves had been illegal in the U.S. since 1807, but selling them remained profitable on the eve of the Civil War. In 1860, Timothy Meaher, a prominent Alabama businessman, sent one of his ships to West Africa on an illegal slave-running mission. But the conspiracy sprang leaks, and by the time the ship arrived back in Mobile, federal prosecutors were asking questions. Meaher stashed most of his human cargo on land he owned up the river from his plantation and burned the ship that brought them.

Then came secession and war, and the Africans upriver were mostly forgotten. They established their own community, hunting and fishing like they had back in Africa. For generations they spoke their own language and preserved African customs and traditions in a neighborhood that came to be called Africatown, a few miles north of downtown Mobile. Africatown survived as a distinct community up to the 1950s.

Another community of African-Americans was taking shape at the other end of the country.

Members of the Darling and Griffin families settled on Malaga Island just after the Civil War, mostly because they needed a place to live. The island, just off one of the countless rocky peninsulas that make up the coast of Maine, was no good for farming, but they were able to build ramshackle houses on the piles of shells left by the tides. They squeezed out a living on whatever fish, lobsters, clams and berries they could find, sometimes doing laundry or odd jobs on the mainland. Theirs was a marginal existence in a marginal place, but it was their place.

Their hardscrabble lives weren’t that different from thousands of others up and down midcoast Maine – or in a thousand other places where the land meets the sea. But the Malaga Islanders were “a peculiar people,” as a local paper described them: Some were black, some white, some mixed race, making them a “queer colony” some saw as a threat.

By the early 20th century, racism came wrapped in science: The eugenics movement, then popular even in sophisticated circles, argued that intelligence, morality and other attributes were hereditary, that interracial coupling produced “feeble-minded” offspring prone to criminal behavior.

There were other complaints about the “Malagaites.” They were poor, and people complained the aid payments needed to help them survive winters had become a drain on the taxpayers. Tourism was coming to coastal Maine, and the shacks of Malaga spoiled the view. Businessmen and politicians wanted a resort on the island, not a bunch of mixed-race “paupers.”

Malaga became the center of legal and political battles, as Phippsburg leaders tried to shed responsibility for the island. Newspapers started spreading rumors about the islanders. They were said to be escaped slaves from the South, or the illegitimate children of slave traders. They were described as “degenerates” living under conditions too “revolting” to describe.

Then, in 1911, backed by a dubious court ruling, Gov. Frederick Plaisted ordered the islanders evicted. Some dismantled their homes and tried to land somewhere else on the coast. The houses still standing on July 1, 1912, were burned to the ground. After a state-ordered “examination,” eight residents were confined to the Maine School for the Feeble-Minded. Since then, no one has lived on Malaga Island.

The end came more gradually for Africatown. It became a neighborhood of Mobile, as heavy industry grew around it. Community members moved away. The children went to public schools and the old language and customs faded away.

Not much remains today: A faded sign stands in front of what once was a welcome center. A crumbling mural features greetings from African leaders. In one corner of a cemetery across the street are the rough graves of the last slaves brought to the U.S. Even communities long gone live on in their cemeteries.

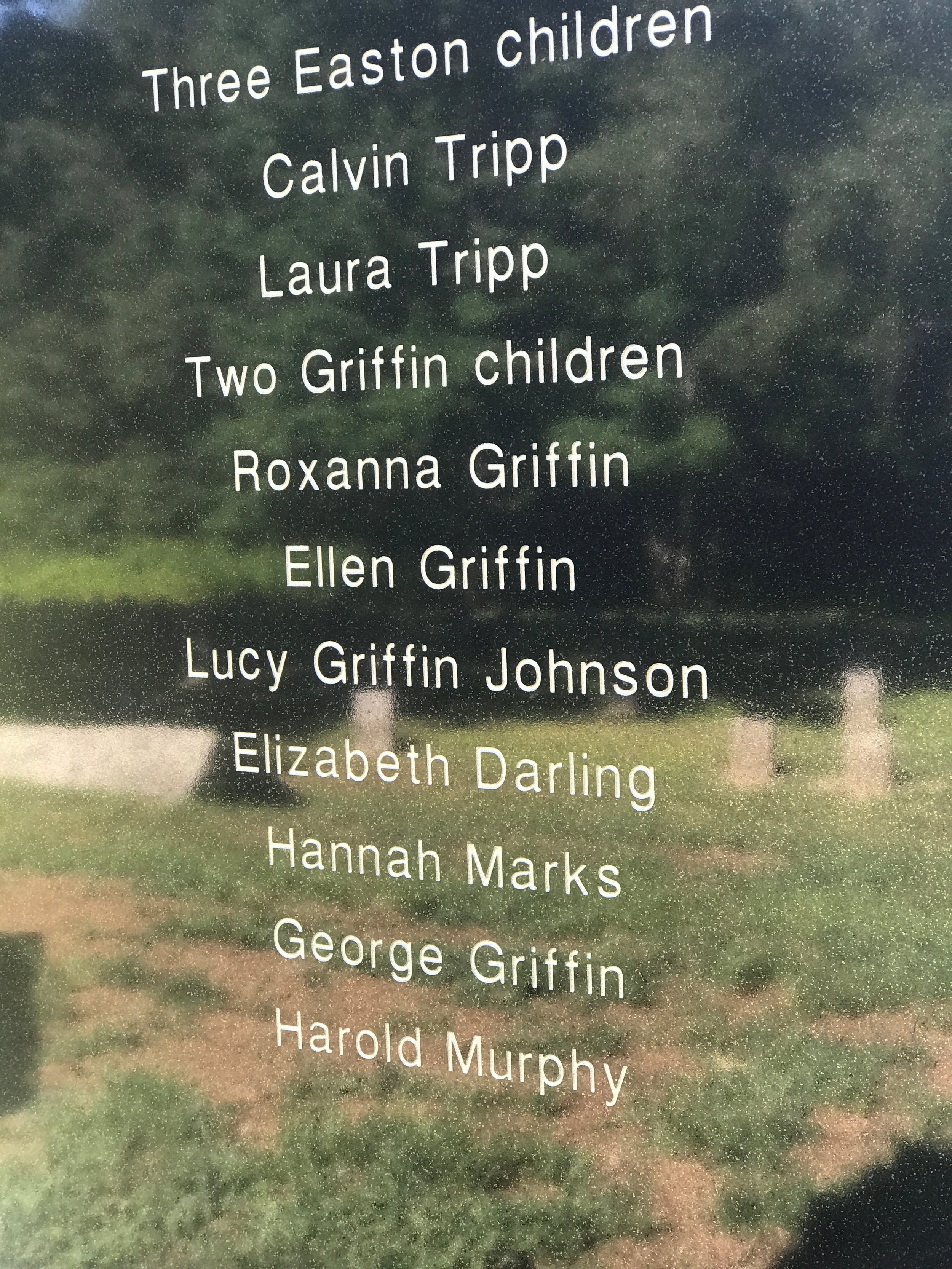

But not on Malaga Island. A few months after the people were evicted, their homes burned down, and their school relocated to another island, the state had the remains of ancestors and relatives buried there dug up. They were buried again on the grounds of the Maine School for the Feeble-Minded.

As Marilyn Darling Voter, a descendant of Malagaites, told the Portland Press-Herald, “Removing the bodies was the difference between eviction and annihilation.”

For nearly a century, what happened on Malaga Island went mostly untold. Then people started telling it. Descendants of the islanders found their voice. Archeologists and historians started digging on the island. An exhibit opened at the Maine State Museum. Journalists rediscovered Malaga.

It’s a nature preserve now, a short kayak ride from Phippsburg. There’s a nice trail winding through woods rich with moss-covered boulders, and a few markers explaining its history. Local lobstermen store their traps on Malaga, and a few tourists stop by, but mostly it’s quiet.

Eventually, the Legislature and governor officially apologized for the shameful acts of their predecessors toward the Malagaites, an apology repeated last month by Gov. Paul LePage at the dedication of a new monument on the grounds of the long-closed School for the Feeble-Minded.

Why all the attention to a century-old crime, long after the victims and perpetrators have died? An inscription on a bench at the new memorial gives a reason: “To know your family history is to know your self.”

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo