Giving voters a second choice

Maine 's experiment in election reform

By Rick Holmes

June 22, 2018

Augusta, Me. – When it comes to political parties, more Americans consider themselves independent than consider themselves either Republicans or Democrats.

Maine has more than its share of independent voters, and independent candidates as well, with a record number expected to appear on ballots this fall. Some have been very successful, most prominently U.S. Sen. Angus King, who served two terms as governor before being elected to the Senate. Other independent and third party candidates have spotlighted issues, offered alternative visions, enlivened debates -- and been denounced as spoilers for siphoning votes away from similar candidates who might otherwise have won.

That’s the dilemma forced on voters by independent or third-party candidates. You can’t vote for the independent you like best without taking a vote away the candidate you like second-best – and improving the chances of the candidate you like least of all. You want to vote your heart, but your head says don’t waste your vote on someone who can’t win.

Mainers have a lot of experience with spoiler candidates and wasted votes. In its 2010 governor’s race, an independent candidate, Eliot Cutler, was blamed for the election of Paul LePage, a Trump-like Republican who only got 37 percent of the vote. Four years later, Cutler ran again as an independent, with similar results. LePage was re-elected, but he still didn’t get a majority of the vote.

That’s not unusual: Nine of the last 11 Maine governors were elected with less than 50 percent of the vote; five with less than 40 percent. But the abrasive and controversial LePage inspired Maine’s voters to try something different.

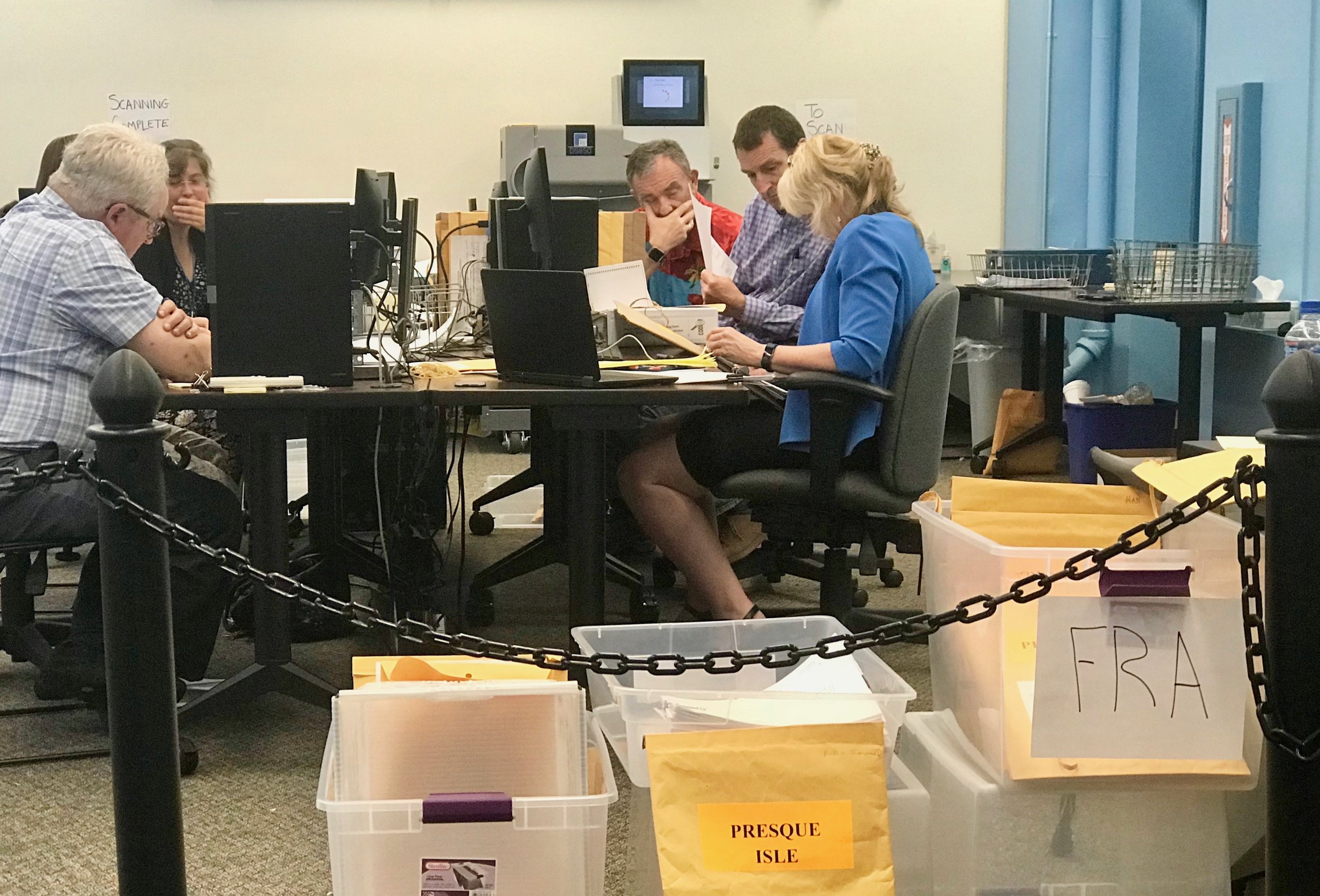

That’s why, on a sparkling June day in Maine, I found myself driving down country roads lined with lupines and wild roses to a brick building across the river from the State House. Hand-written signs designated a nondescript room as the center of an electoral experiment: the first use of ranked-choice voting in a statewide election.

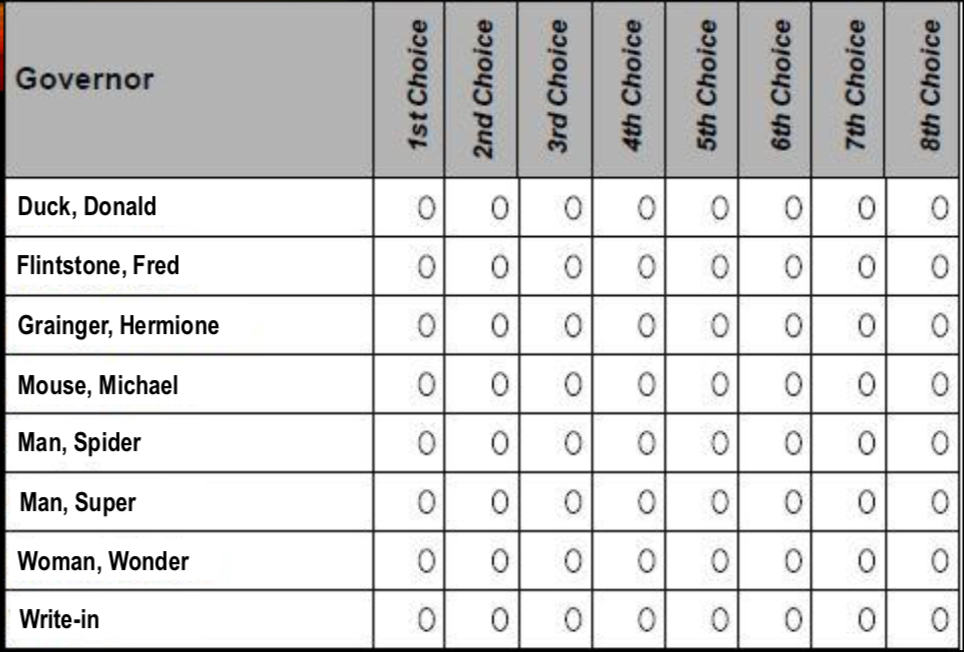

Ranked-choice voting is more difficult to explain than to do. Under ranked-choice, a system already in use in other countries and several U.S. cities, voters choose candidates in order of preference. If no candidate has a majority after all the first-choice votes are counted, the candidate with the lowest total is eliminated, with his votes allocated to whoever those voters chose second. The process continues until a candidate reaches 50 percent of the vote.

Backers of the reform say it not only selects candidates with a clear majority of votes, it encourages candidates and campaigns to be more moderate in tone, so as not to offend supporters of an opponent who might throw them a second-choice vote. It also, theoretically at least, encourages more voter engagement, as people have to study the candidates more closely to figure out who they like second best, third best, and so on.

Maine voters adopted the new system over the opposition of the state’s Republican and Democratic establishments, who fought it in the courts and the state Legislature, which repealed the voter initiative. LePage fulminated against the reform, which likely would have kept him from winning the governor’s race had it been in effect in 2010, declaring it too confusing for Mainers.

The new system got its first chance in the June 12 state primary, and voters didn’t find it all that confusing. "If people can get American Idol, how can you not get this?” a Portland voter told Maine Public Broadcasting. “Gimme a break.”

State election workers spent a week in the nondescript room certifying ballots and creating a database, then a laptop computer counted, sorted, allocated second-choice votes and produced winners.

In the end, the results were unsurprising. Janet Mills, who led with 37 percent of the first-place votes in the first round, picked up enough second place votes from backers of five eliminated candidates to win the Democratic nomination for governor with 54 percent. Ranked-choice factored in just one other race, the Democratic primary for a U.S. House seat representing the northern part of the state, and the winner of the first round came out on top there as well.

There was no clear result on the experiment’s other questions. The campaigns weren’t notably more civil than expected. Some voters were more engaged by the process, saying they studied the candidates more closely, and turnout was high, but we’ve seen higher engagement in races across the country this year. We don’t know how people would react if a candidate who had received the most first-place votes was defeated when the second choices were figured in. Nor have we seen yet how campaigns would try to game the new system.

But one clear winner in Maine’s primary was ranked-choice voting itself. Through a ballot question, voters repealed the Legislature’s repeal of ranked-choice voting, which means the new system will be in place for November’s Senate election, in which independent Sen. Angus King will face Republican and Democratic challengers.

Without a time machine, we can’t know whether ranked-choice voting, by counting the second-choices of those who voted for Ralph Nader in 2000 or Jill Stein and Gary Johnson in 2016, would have changed presidential history. But Mainers are happy to make spoiler candidates and wasted votes a thing of the past.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.