The mill, the mountain and the monument

When a company town loses its company

By Rick Holmes

Sept. 29, 2017

Millinocket, Me. – Millinocket is one of those left-behind places. The old economy is gone and the new economy has yet to arrive.

Millinocket and the other hard-scrabble towns here in inland Maine have one advantage: the beauty of the wilderness that surrounds them. Mt. Katahdin, the state’s tallest peak, looks down on deep woods and pristine waters that draw thousands of visitors each year and could attract many thousands more – if politics and distrust of Washington don’t mess it up.

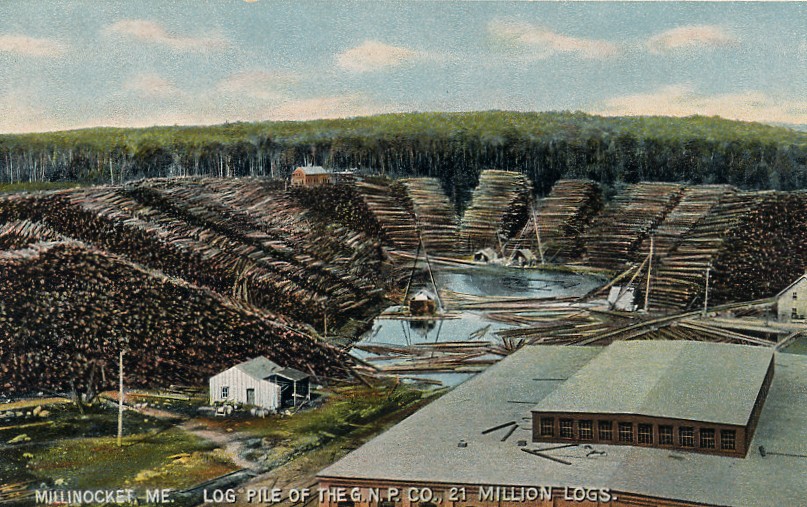

Millinocket is a company town. In 1900, Great Northern Paper Co. built the largest pulp paper plant in the world here, and a town grew around it so fast it became known as “Magic City.”

Great Northern supplied the newsprint on which the great newspaper wars of the early 20th century were fought. Great Northern grew, opening new pulp paper plants and buying land. By the 1940s, it owned more than 2 million acres in northern Maine, and just about everything that moved in Millinocket. Loggers would cut the trees and float them down the Penobscot in great “log drives” to the mills below.

But hard times came to the pulp paper industry, and locals blame environmentalists and federal regulators for some of it. The feds declared log drives to be bad for the rivers, Trudy Wynan, curator of the Millinocket Historical Society Museum, told me. Then the feds made paper companies clean up the rivers they’d polluted for decades, and stop poisoning the air with noxious smokestack emissions.

Great Northern had other problems. The newsprint market dwindled along with newspapers. Grocery stores stopped using brown paper bags. Canadian pulp plants unfairly undercut U.S. manufacturers, at least according to U.S. officials.

Great Northern got caught up in Wall Street’s debt-fueled mergers and acquisitions battles. The company was sold, then sold again, with each new owner less committed to the people of Millinocket than the last. The mill was eventually sold to an investment firm with little interest in making paper, which then sold it to a salvage company.

“We sat on the porch and watched the big trucks haul the paper mill away,” Wynan said.

When a company town loses its company, there’s not much left. Great Northern discouraged other industries because it didn’t want to share its labor pool.

Millinocket’s young people have been leaving town for 30 years, she said, and while a few have returned and are trying to bring some entrepreneurial energy to the abandoned mill site, they’ve got a long way to go.

But while cleaning up its air and water pollution may have hurt the paper industry’s bottom line, it made the area even more attractive to the backwoods set. Mount Katahdin, the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail, draws backpackers from all over the world. Whitewater rafting, hunting, fishing and off-road riding, draw thousands more.

The beauty of the region inspired a wealthy benefactor, Roxane Quimby, who quietly bought up more than 87,000 acres east of Mt. Katahdin and spent years trying to give the land to the federal government for a new national park. Those efforts paid off last year, when President Barack Obama announced the creation of the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument. Quimby then pledged $40 million to get the new park up and running.

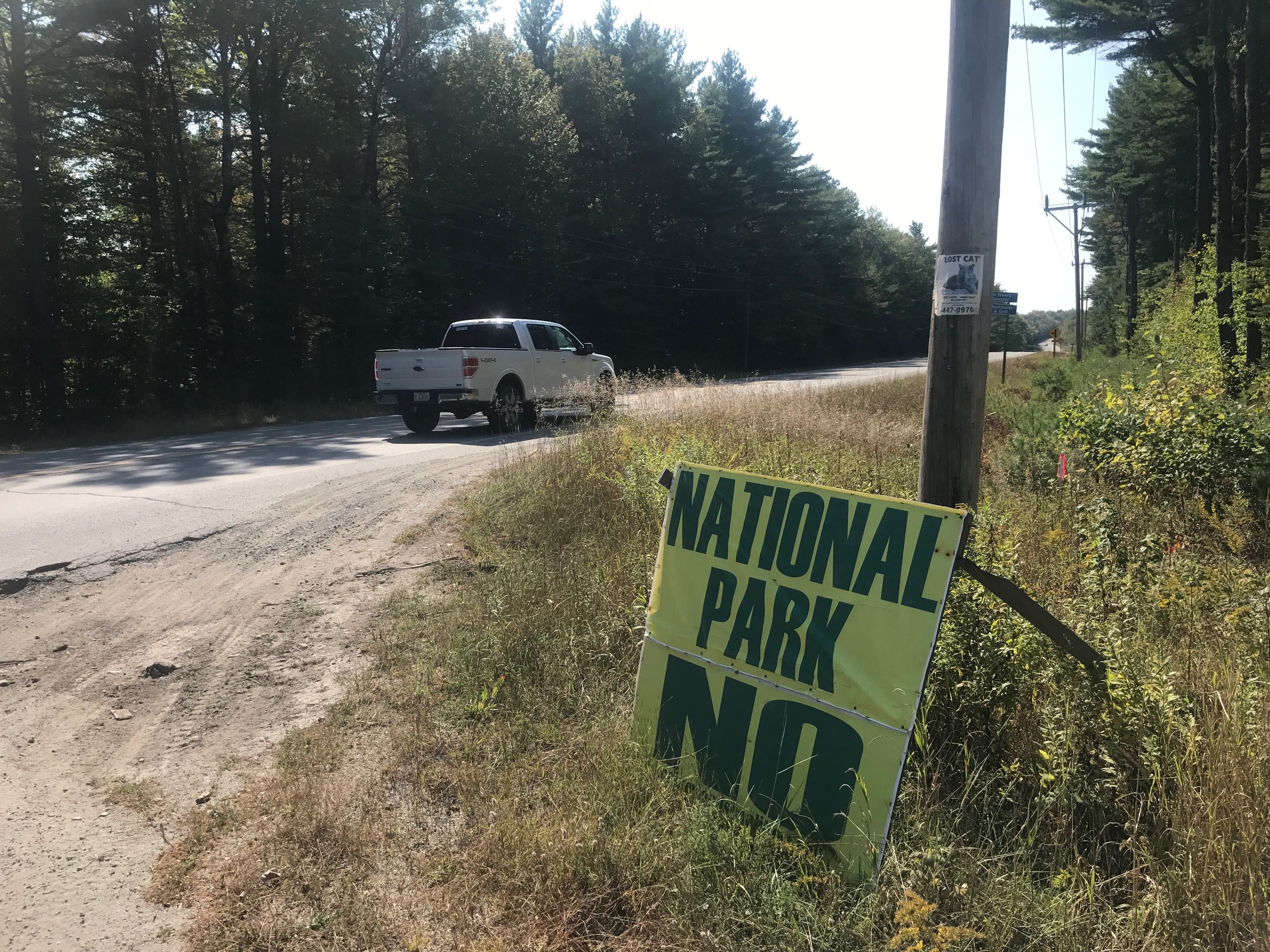

There was opposition from the start, and “National Park NO” signs still dot area roads. The logging companies are against it. Some locals worry about losing access to land for hunting or snowmobiling, though there will still be plenty of opportunities for both. People are suspicious of the federal government and of outsiders like Quimby.

Among these is Gov. Paul LePage, who has done everything he can to stop his state’s newest park. Even now, with the national monument officially open to the public, LePage refuses to let signs – already purchased by the KWW – be posted on the interstate or any roads leading to the park.

There was national opposition as well, from conservatives who contend Obama and some of his predecessors have abused the power to create national monuments under the 1906 Antiquities Act. Candidate Donald Trump opposed Obama’s designations and promised to undesignate them. He ordered Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to re-evaluate several dozen recently-created national monuments, including – at LePage’s pleading – Katahdin Woods and Waters.

No one knows what Trump will decide, so uncertainty lingers over the KWW. Supporters of the new park say locals are coming around to the idea, but there’s still grumbling. People don’t want a lot of tourists changing their little towns. They don’t want traffic jams and low-wage seasonal jobs. They want the old days, with good jobs for everyone down at the paper mill in their little company town.

But those jobs are long gone. What’s left is the mountain, the land and the opportunity that comes with the gift of an outsider.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo