The power of America’s stories

By Rick Holmes

Nov. 23, 2018

Bowie, Maryland – In a windowless brick room in the Belair Mansion, a modest exhibit tries to tell the story of hundreds of enslaved people who lived there. There’s not much to work with: Ledgers note some of the names they had been given – Liza, Negro Pompey, Little George, Rachel, Darkey and Ben – and their dollar value. Beyond that, a printed guide concedes that “records to date have revealed nothing about slave lives at Belair.” Their masters, Maryland aristocrats who introduced thoroughbred horses to the New World, are remembered. The people they bought and sold are all but forgotten.

The exhibit tells one story involving some of the people owned by the Ogle family, masters of Belair. During the War of 1812, while the British occupied Washington, DC, they proclaimed all enslaved Africans who came over to the British side would be granted their freedom. About 40 slaves working on Ogle properties slipped away in the dark of night and rendezvoused with a British ship moored off Diggs Point on the Chesapeake Bay. We don’t know what happened to them after that, but none were ever recaptured.

That’s the kind of story that ought to be told as America continues to come to grips with its history. We need to hear not just the stories of suffering under slavery, but the stories of resistance and escape, not just stories about how Lincoln freed the slaves, but what they did to free themselves.

Maryland has many such stories, and they are being told like never before. Because it’s a coastal state, close to the north, escape was always a dangerous option for Maryland slaves. Most of those who escaped were little-known, like those who slipped away at Diggs Point. But three who escaped bondage in Maryland lived to tell their stories, becoming famous in the process and helping change the course of our nation.

Josiah Henson escaped to Canada in 1830, where he became a minister, founded a community for fugitive slaves and wrote an autobiography. His story inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which helped turn millions against slavery.

Frederick Douglass escaped from Baltimore in 1838. He told his story in three best-selling autobiographies, and went on to lead the abolitionist movement and become the most celebrated African-American of his times.

Harriet Tubman escaped from the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in 1849, but she didn’t stay away for long. She returned at least 13 times to guide other slaves, including many in her family, north to freedom on the Underground Railroad. She couldn’t read or write, so she told her story in speeches. She became a leading abolitionist, then a leader of the Women’s Suffrage movement.

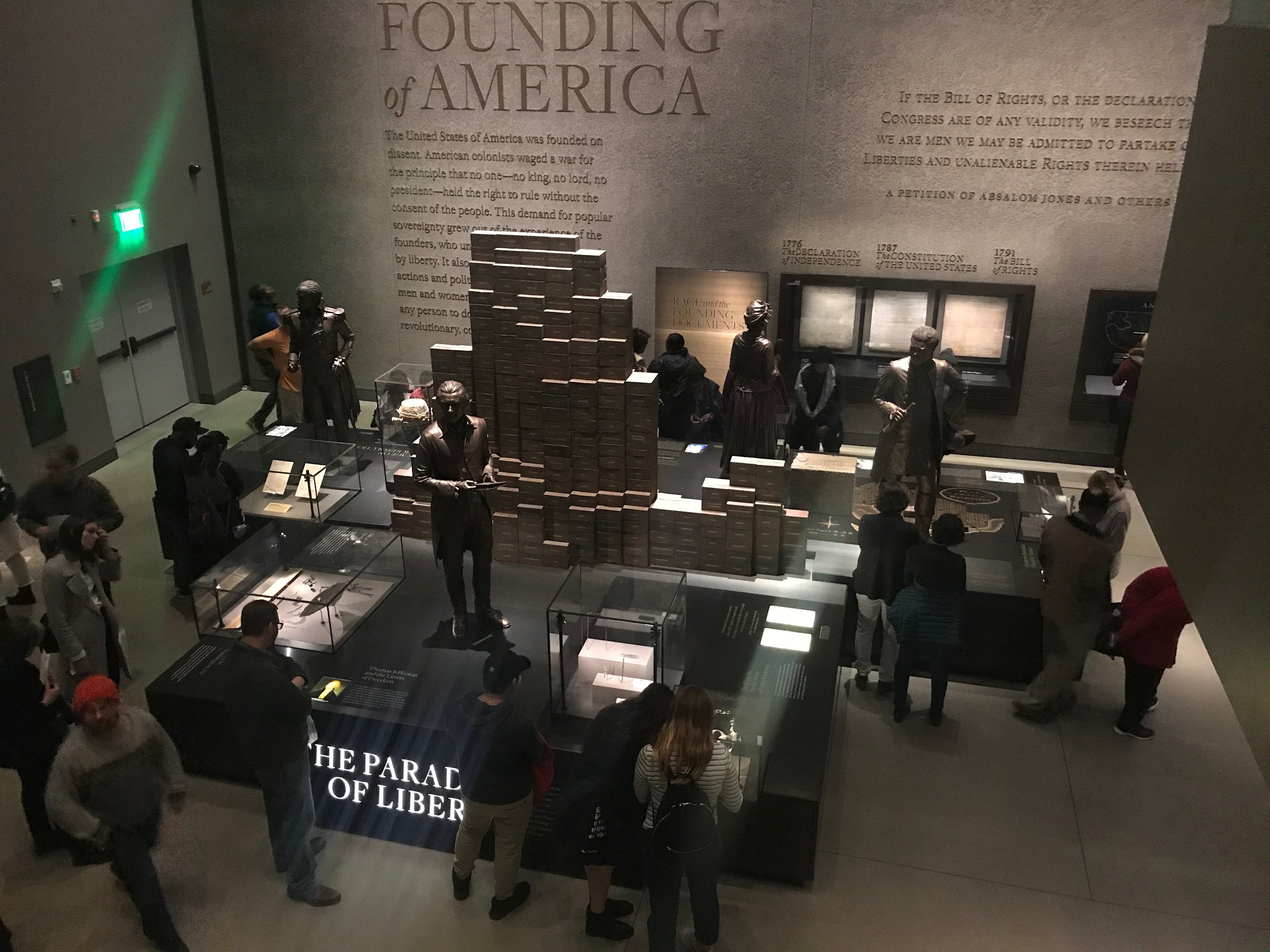

Their stories are among the hundreds told in the Smithsonian’s newest museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture. More than 4.5 million have visited the handsome building at the foot of the Washington Monument since it opened two years ago. Tickets are free – thanks, Smithsonian – but you’ve got to book them months in advance or get up early to grab an online pass the day of your visit.

It’s worth the effort. The museum covers 500 years of history with broad brushstrokes and revealing details. A floor devoted to African American culture – art, theater, cuisine and especially music – is as thrilling as the history is sobering. Not only does the museum tell stories from America’s past, it provides booths in which visitors can record their own stories, which are added to the museum’s collection.

Stories are powerful things. Personal stories, told with conviction, expand horizons and build empathy in the listeners. Historical stories, told with respect for the truth and compassion for all involved, build community.

Recently, America has picked up the pace of its storytelling. People are rediscovering the past, and looking at it from different perspectives. New memorials are being raised, commemorating events previously buried and recognizing heroes previously ignored.

The story of Harriet Tubman, the greatest conductor on the Underground Railroad, is now being told in a new national historic park on the edge of the Blackwater Wildlife Refuge on the Eastern Shore. A new museum is being built in North Bethesda to tell Josiah Henson’s story. Earlier this year, a statue was unveiled at Philadelphia City Hall honoring Octavius Catto, an educator and civil rights activist killed during Election Day violence in 1871. And we’ve made room on our National Mall – often called “America’s front yard” – for the stories of generations of African Americans.

We’re always being told how divided America is, and in some ways it’s true. But behind the shrill arguments of politicians and media agitators, something else is happening. Americans are quietly learning new stories that broaden our understanding of who we are and where we came from. Those are America’s stories, and they hold the power to knit a constantly-changing nation back together.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.