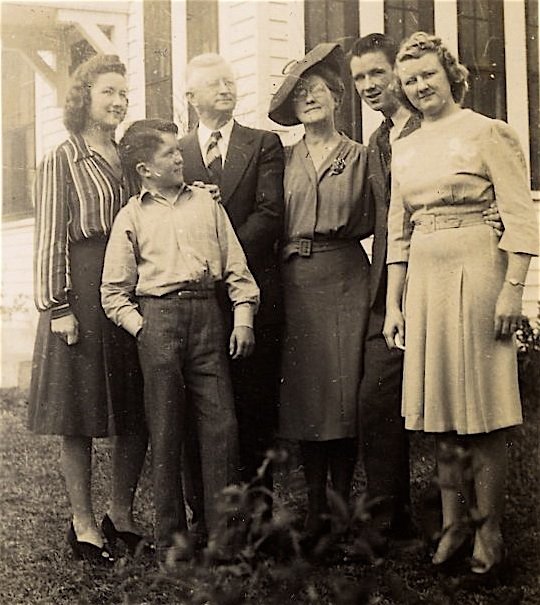

Mabel Boyd Davis and Oma Grier Davis, circa 1906

8. Oma Grier, Mabel and ‘the work’

Grier and Allie’s middle child, Oma Grier, was born in 1885. He was just 12 when his father died, and in many ways he was his father’s son. “He was a leader in the family when he was 12,” his daughter Lily said. Soon after his father died, Oma developed a malignant tumor on his tongue. It had to be “burned out,” according to one account, “a torturous 7-hour operation without anesthesia. He promised God at that time that if he recovered and could talk well, he would give his life to the ministry. He had a remarkable recovery, and without any speech impediment.”

Oma the serious boy grew to be the Rev. Dr. O.G. Davis, a serious man dedicated to church and passionate about education. He trained to be a Presbyterian minister, earning degrees from Davidson College and Princeton University and a doctor of divinity degree from Arkansas College.. He was a stern man, a man of deep thought and high standards. “Writing history is more than the mere recording of foregoing events,” O.G. wrote in 1916, “It is a mighty means for building high ideals and fostering worthy aspirations.”

In 1914, Oma married Mabel Boyd, who was the perfect complement to his seriousness. They and their children later delighted in a tale from O.G. and Mabel’s courtship. They were riding a horse-and-buggy along Drew County’s muddy rutted roads one day, O.G. wearing a new hat, a bright white straw skimmer. The buggy hit a pothole and O.G.’s hat flew off, landing in a mud puddle. O.G. leaped out to rescue the hat, his consternation growing as he feverishly wiped at the hat with a handkerchief, mostly just spreading the stain further. Mabel tried to stifle her giggles at the situation, but she couldn’t hold in her laughter. “I don’t see anything funny about ruining my hat in the mud,” O.G sputtered. “You are a frivolous woman, Mabel. Why do you always laugh at the wrong time?”

Rev. O.G. Davis’ first calling was to a small A.R.P. church in Cotton Plant, Mississippi. There he determined to put his educational theories to the test. He wanted to see the schools of rural Tippah County consolidated into a big school, that would work with churches for the betterment of all. School consolidation was controversial everywhere in the 20th century and still is, in some places. This time the young minister, for all his enthusiasm, couldn’t convince his neighbors. As Mabel Boyd Jr, who I knew as Aunt Mame, later wrote (with a turn of phrase appropriate to cotton country): “when two years of constant wooing failed to bring the people to see his vision he began to look about for fields more white for the harvest.”

That next stop was Dardanelle, Arkansas, where O.G. was called to a church where Mabel had earlier directed activities for youth. It proved to be a door O.G. took out of the small Associate Reformed Presbyterian denomination into the far larger Southern Presbyterian Church. Davises had followed the ARP from Scotland to Carolina to Arkansas. It was a conservative sect. Meals to be eaten on Sunday had to be prepared the day before. No musical instruments were allowed in church, only the human voice, and even that was limited: only psalms could be sung at worship on Sunday, no hymns.

Theological distinctions aside, there were more career opportunities in the larger Presbyterian Church, and one soon arrived. O.G. was named Superintendent of Home Missions for the Mississippi Presbytery, and embarked on what would be his life’s work: founding and building new churches to spread the gospel. He was initially based in Blue Mountain, Miss., where he also served on the faculty at Blue Mountain College, teaching French and education, but he moved his family often during those years, as the work demanded.

Mabel was a full partner in what they called “the work.” The couple would go door to door in the targeted community, gauging interest and signing up prospective church members. O.G. was a skilled carpenter as well as a teacher and preacher, and once the church was organized and a site was found, he began building a church and, often, a manse for the minister’s family to live in. He built the pulpit and preached the sermons; she ran the Sunday School, the music ministry and the Women’s Auxiliary. When the church was established, they moved on to the next. In all, they built 17 churches from scratch, most of them in Mississippi and Louisiana.

The work brought the Davises back to Tippah County, where O.G. returned to his goal of a consolidated school connected to the church. This time he had success, creating a school that by 1923 had enrolled 200 students. Again, he was a builder as well as a visionary. A sawmill was erected on the site, where trees were made into lumber on the spot for campus buildings. He built a dormitory to house up to 30 boarding students, but first it housed his family, which now included four young children. It was called Peoples’ Consolidated School, and the small community that grew around it was called Peoples. A century later I tried to find some sign of the long-closed school, believed to have been in the Ripley, Miss., area, without luck.

Once the school had graduated its first class, O.G. was ready to move on. He enrolled in a doctorate program at George Washington University, and found a small church outside Washington, DC, where he could serve as interim pastor – and house his family in the manse – while he studied. That led to a commission to found and build a new church in Baltimore that is still active. In Jennings, Louisiana, he converted a Congregationalist congregation to Presbyterianism and became its pastor. From there he was called to Baton Rouge, where he organized and built the Northside Presbyterian Church and a manse nearby. That’s the church where he presided over my parents’ wedding, so I went looking for it during a visit to Baton Rouge, working from street signs in old photographs. All I found was Interstate 110 where the church used to be.

O.G. got sick in 1943, apparently a heart ailment, and his health grew steadily worse. In 1945, Mabel took him to Minnesota for six weeks of treatment at the Mayo Clinic, but the prognosis wasn’t good. “He was never really well afterward,” Mabel writes. “His heart was stricken, and he could keep going only with great care.” That meant he couldn’t handle the work of a pastor in a large church like Northside, and if he couldn’t be the pastor, his family couldn’t stay in the manse.

The O.G. Davises never had much money. They lived in a poor part of the country and depended on donations to the church. During those Depression years, the collection plates couldn’t have yielded much. I find it striking that, after several generations of Davises dedicated to acquiring land for their children, Oma Grier never owned real estate. He and his family lived in rented flats, and in church manses, some of which he raised money for and built with his bare hands. That includes the dormitory of the People’s School, where Mabel and four small children lived without electricity, running water or at times even a roof over their heads, and Northside Presbyterian in Baton Rouge, where O.G. and his son Oma Grier slept on the floor while they built the manse walls around them. In every case, they gave what they’d built to the community and moved on.

It wasn’t an easy life for Mabel and their five children, following O.G.’s callings. My mother, Allie Coleman Davis Holmes, moved from Cotton Plant to Dardenelles when she was just one month old, and went to three different elementary schools. Father was away most every weekend and busy always. But the tightness within the family, and the support of the church communities surrounding them, more than made up for interrupted childhood friendships. They were all dedicated to O.G. and “the work.” I never heard a word of criticism from my mother, and in Mabel’s memoirs there’s not a hint of regret.

In 1946, O.G. and Mabel left Baton Rouge pulling a small trailer stuffed with as many belongings as it could hold, looking for a low-stress church with a vacant manse. His heart was weak. He needed help getting up the stairs on their first stop, and it was decided son Charles, then just 15, would have to drive. But they made it safely to Thompson Valley, Virginia, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Church and community welcomed the frail new pastor with open arms. Once they learned of O.G.’s skills, they prevailed on him to build a new church in a more central location. He agreed to manage the project, but it was one mission he couldn’t complete. He suffered a heart attack and died on Easter Sunday, 1947, at age 62.

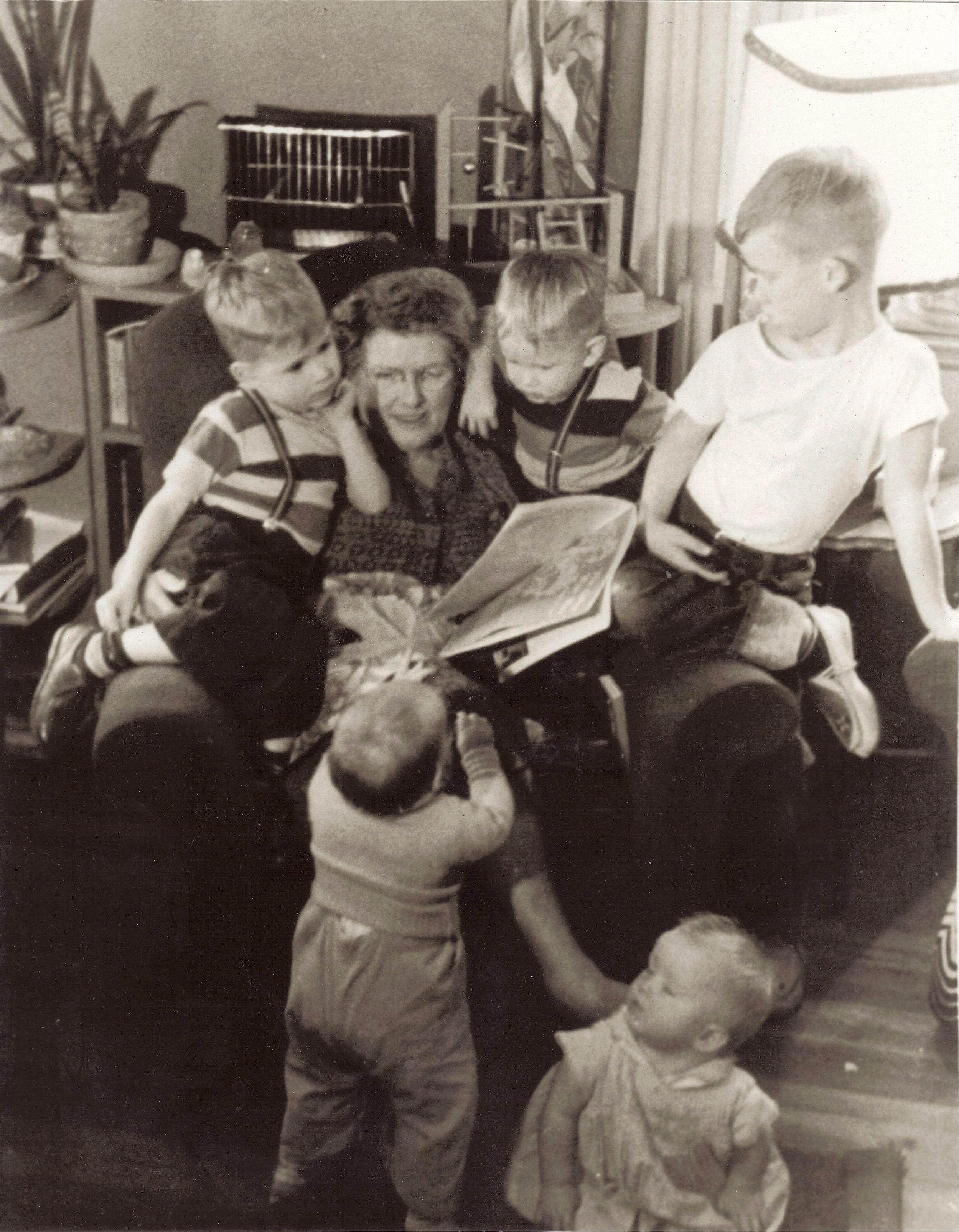

The following Sunday, church elders asked Mabel to please stay on in the manse and supervise the completion of the new church building. She was reluctant – construction hadn’t even started and planning was moving slowly on the long-delayed project. But she agreed, put her mind to it and delivered a fine new church. She continued to teach, for several years in Princeton, NJ, and finally back in Thompson Valley, where she and Mame built the first house they ever owned.

Mabel was the musician in the family, a love she passed on to her children. Oma Grier didn’t produce any ministers of the gospel, but four of their five children grew up to be choir directors. Mabel was an artist, whose oil paintings adorn the walls of her grandchildren today. She died in 1963, at age 75. We called her Muna, and she’s a luminous figure in my memory, the only grandparent I really loved.