Highway to nowhere

Route 66 is off the maps, but its mystique survives

By Rick Holmes

May 5, 2018

Eureka, Mo. -- How do you explain Route 66 to people born after its magic number disappeared from the maps? It’s hard enough to explain maps to people who let their phones do the navigating.

Already, it’s difficult to find anyone outside of assisted living who remembers when paved highways were new. Back in the 1920s, when driving faster than 20 mph on rutted dirt roads was a bone-rattling slog through dust and mud, asphalt was a revelation.

Americans took to the paved wonders of the new U.S. Highways for the pure joy of high-speed, dust-free travel. Sunday drives became the new pastime. Businesses opened up just to give those motorists a reason to pull over for a break: Roadhouses featuring steaks and home cooked meals, gas stations that celebrated their mission, ice cream stands, miniature golf courses and modern motels where you could park right in front of your cottage.

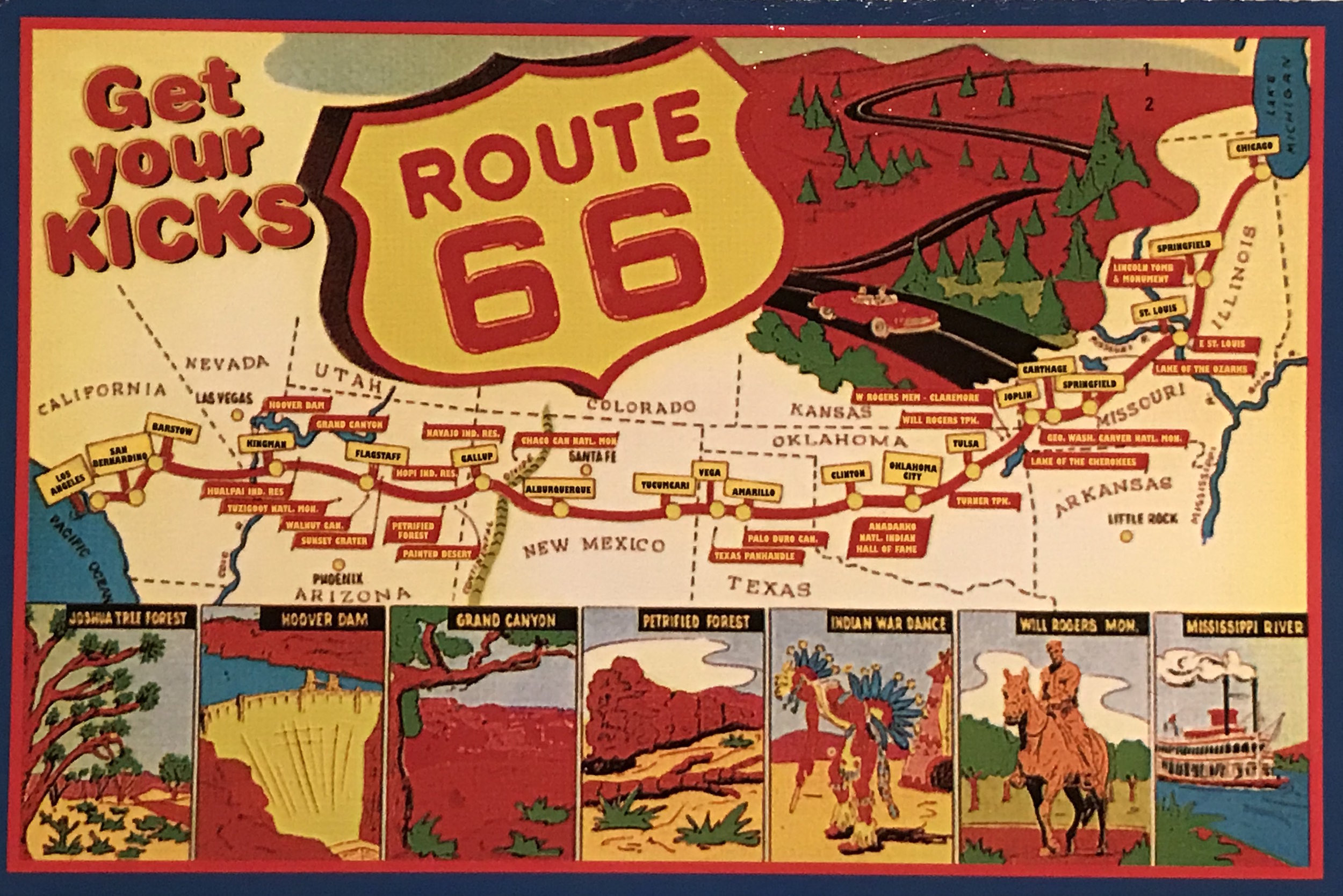

The most famous of these roads was Route 66. Built in 1926, Route 66 started in Chicago, crossed the Mississippi at St. Louis, shot through the plains of Kansas and the deserts of the Southwest, ending in Los Angeles, city of American dreams.

“Get your kicks on Route 66,” sang Nat King Cole in a hit still performed today. In the early 1960s, a new generation of Americans embraced the romance of the road. In the TV series “Route 66,” two footloose, handsome young men in a Corvette Stingray roamed the highway, finding adventures at every stop.

One stop on this stretch of Route 66 witnessed a different kind of adventure.

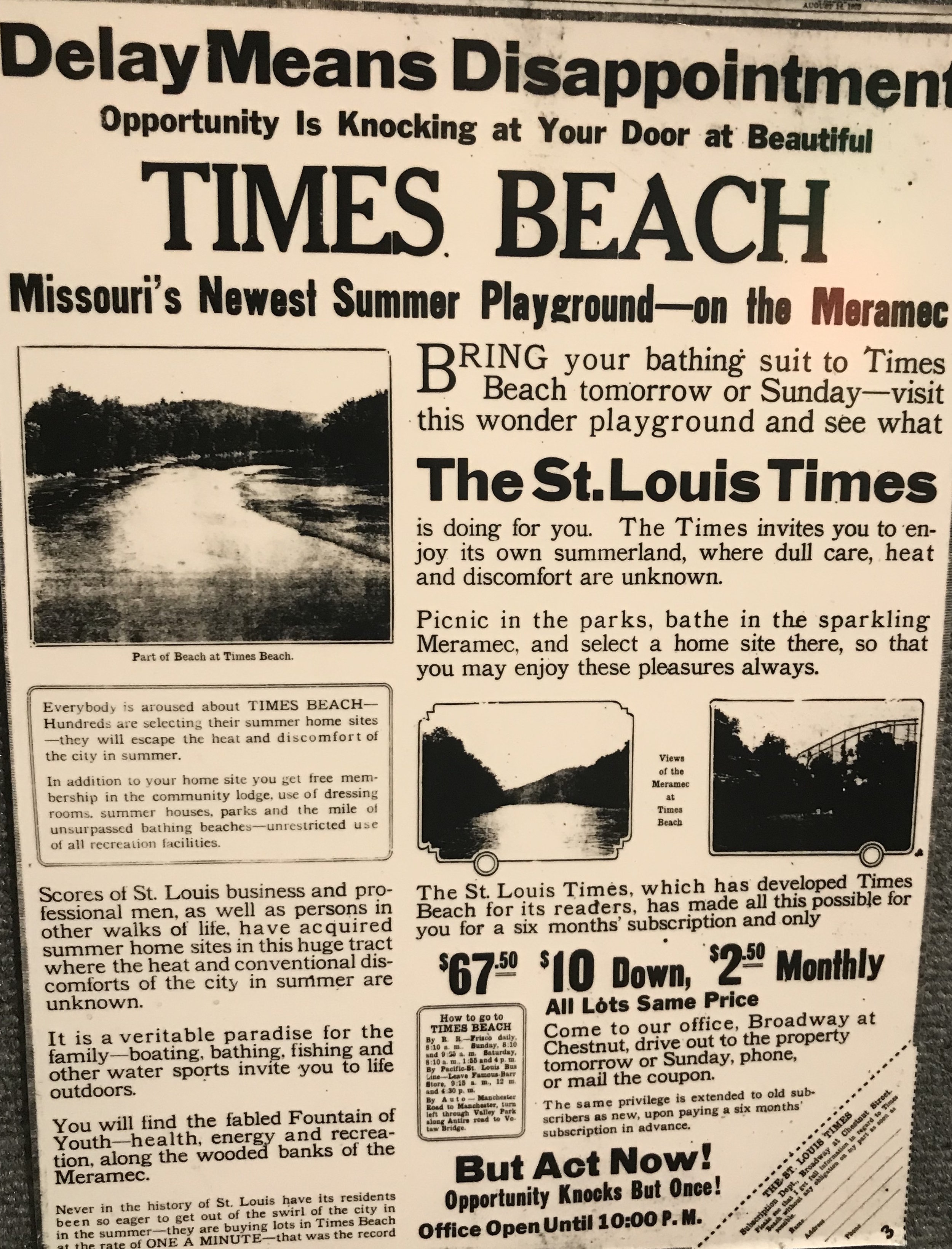

Times Beach was a town that started as a newspaper promotion. If you bought a six-month subscription to the St. Louis Star-Times, you could purchase a tiny lot – just 20 feet by 100 feet – in the resort then being built on the banks of the Meramec River. When Route 66 was built, crossing the river at Times Beach, it became an even more popular destination for those seeking refuge from the hot St. Louis summers. Over time, tents and trailers parked on the lots gave way to summer cottages, then year-round homes for people who couldn’t afford something bigger closer to town.

By 1970, more than 1,200 people lived in Times Beach, most of them pretty poor, and the town still couldn’t afford to pave its roads. So they hired a guy named Raymond Bliss, a waste oil hauler, to spread oil on the streets to keep the dust down. Through a combination of his stupidity and inadequate government regulation, the oil Bliss spread was laced with dioxin, a deadly poison.

Ten years later, health officials took soil samples in the town, discovering the dioxin just as the Meramec flooded, forcing the evacuation of Times Beach. Before the waters receded and the residents could go back home, federal officials ruled the town was too toxic for human habitation.

The plight of Times Beach generated national headlines and, medical researchers now say, more hysteria than was justified by the threat. The state and federal ended up buying all the homes and businesses, then spending $200 million to clean the area up. The EPA built an incinerator on the property and burned up 265,000 tons of Times Beach topsoil.

In 1985, its 2,000 residents relocated, the Missouri governor officially “dis-incorporated” Times Beach.

Route 66 was dis-incorporated that same year. The Interstate Highway System killed it, replacing some parts and bypassing others. The iconic black-and-white Route 66 signs have all come down, but you can sometimes find signs marking “Historic Route 66” on portions that survive under new names.

People still look for those signs and try to follow the old route from one end of the road to the other, especially retirees, the woman at the visitor center told me. And a surprising number of Europeans, according to the pins in the world map on the wall. “They fly into Chicago, rent an RV and try to find their way to California,” she said. The mystique of the American road isn’t dead yet.

But what do these Route 66 explorers find?

The visitor center is in a bland building that used to be a Route 66 roadhouse. Open since March, it’s the centerpiece of Missouri’s Route 66 State Park – 419 acres of fields, woods, hiking trails built on the decontaminated remains of Times Beach.

Old Route 66 runs past the visitor center’s front door and comes to an abrupt halt at a barricaded bridge over the Meramec River, the bridge that used to take dreamers and adventurers west, to Times Beach and beyond.

The bridge is a rusting skeleton now, with all its pavement removed. It’s all that’s left of a legendary highway that brought Americans and their dreams to a town that has now disappeared.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.