John Brown’s Missing Bell

By Rick Holmes

Nov. 10, 2017

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia – This is a place of history and mystery, memory and myth.

Here, Thomas Jefferson looked out at the confluence of the Potomac and the Shenandoah rivers and called it “one of the most stupendous scenes in Nature.” Here, George Washington saw abundant water power and a strategic location for one of the nation’s first federal armories.

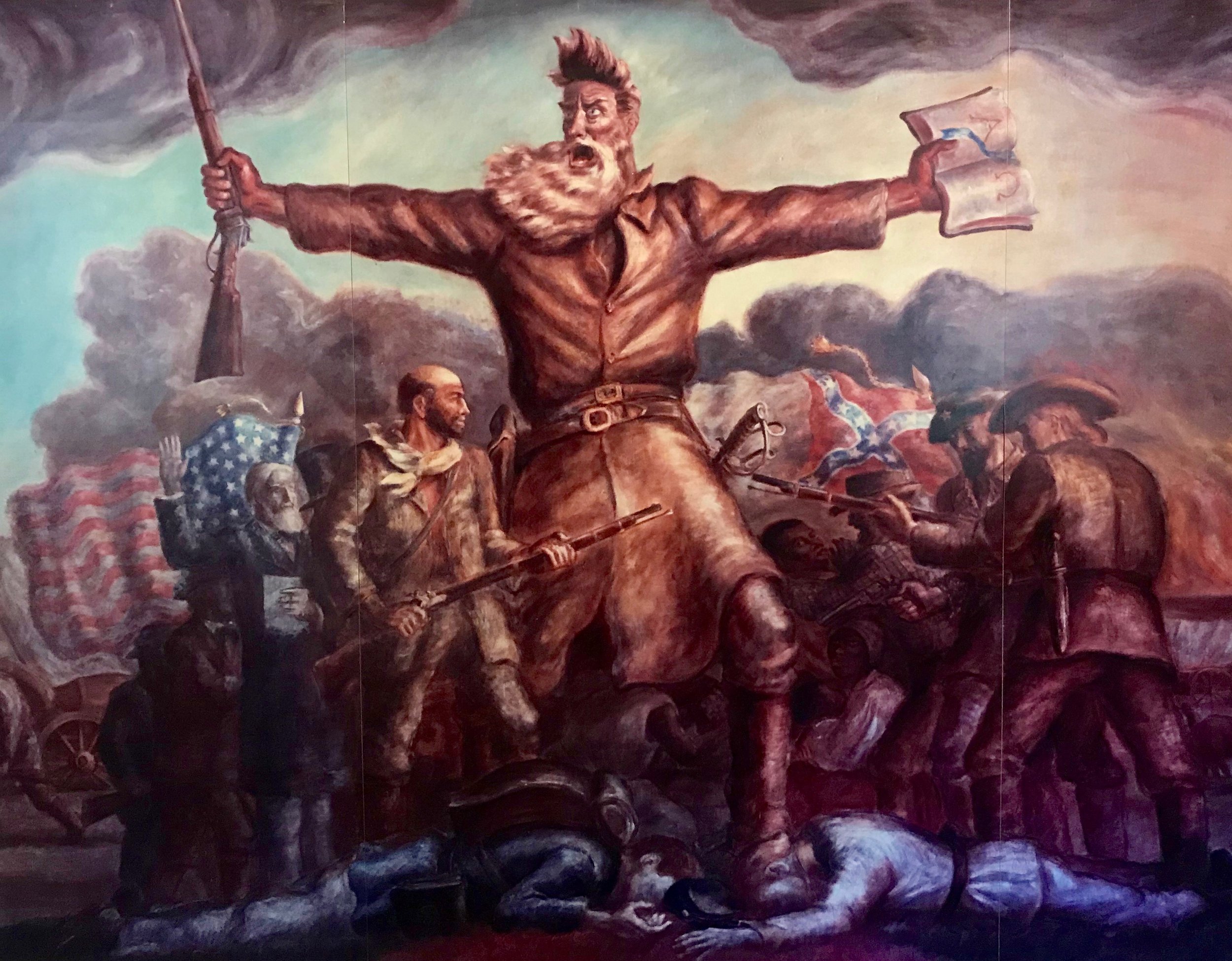

And here, in October 1859, a radical abolitionist named John Brown attempted to start a slave rebellion and ended up inspiring both North and South in the war that would soon engulf them.

Brown and his army of 21 men invaded Harpers Ferry late at night, crossing the Potomac from Maryland. They seized some ground and took some hostages, but soon found themselves taking fire from citizens and members of the local militia. They holed up in a brick fire engine house on the armory grounds until a contingent of U.S. Marines, led by Col. Robert E. Lee, stormed the engine house and took Brown prisoner.

Brown was charged with murder, treason and slave insurrection and became an overnight sensation. His trial and hanging made headlines around the world.

Two years later, Harpers Ferry was a battlefield again. Control of the town changed hands eight times between 1861 and 1865. Much of it was destroyed in the process, including every building in the arsenal compound except the brick engine house.

Between battles, Harpers Ferry was a no-man’s-land that soldiers from both sides visited to hunt for provisions and souvenirs. Among these were the men of Company I of the 13th Massachusetts Volunteers. Their platoon included several firefighters who thought the bell hanging over the engine house would look great outside their hook and ladder company back in Marlborough.

They stole the bell and lugged it back to their camp. But there were battles to be fought, so the men of Company I left the bell with a friend in Maryland, who buried it in her backyard for safekeeping. Thirty years later, when some of the Marlborough veterans returned to the area for a reunion, they looked up their old friend and were surprised to find she still had the bell.

They shipped what became known as John Brown’s Bell back to Massachusetts, where they exhibited it with pride. At one point the bell toured the country with Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell, billed as America’s most historic bells. People imagined John Brown himself ringing the bell to call slaves to rebellion.

But one man’s souvenir is another man’s plunder. John Brown’s Bell has historic value. It is the property of the federal government, which has preserved much of Harpers Ferry in a National Historical Park. Over the years, there have been calls to return the bell to its rightful place atop John Brown’s Fort, as the brick engine house came to be called. Those calls have been repeatedly ignored by the civic leaders of Marlborough, who contend that they stole the bell fair and square. The National Park Service would like the bell back, but hasn’t been willing to fight for it in court.

The controversy inspired the NPS to order up a new study of the bell’s origins that found something surprising. A close examination of records, drawings and photographs led historian Dean Herrin to conclude that there was no bell and no belfry atop the engine house at the time of John Brown’s raid. Both were attached to the building, likely moved from another location on the armory grounds, between the raid and the outbreak of war in 1861.

So the bell isn’t really John Brown’s Bell after all, and the fort, lovingly restored after being disassembled and moved as far away as Chicago, doesn’t really look like it did in 1859.

Ironic, I guess, but does it matter? In his report, Herrin quotes former NPS Chief Historian Dwight Pitcaithley: “Our collected heritage is as much memory as fact, as much myth as reality, as much perception as preservation.”

John Brown’s raid was a folly and a failure. He expected support from the locals and got bullets instead. No slaves joined his rebellion, which lasted all of 36 hours.

But there is power in martyrdom. Brown gave his life for a righteous cause that was gaining momentum. Union troops marched to battle singing that “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave, but his truth goes marching on.”

And the raid enraged Southerners, who had long-standing – and justified – fears of a slave uprising. It didn’t start the Civil War, but it added fuel to the Secessionist fire.

After the war, Harpers Ferry became a mecca for freed slaves and the African-Americans who created the first civil rights movement. It inspired “Lost Cause” romantics as well. In 1931, the Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument there to Heyward Shepherd, a former slave working as a railroad guard, who was the first man killed by Brown’s raiders. It holds Shepherd up as a symbol of the “faithfulness of thousands of Negroes” who resisted the temptation to rise up against their masters.

Harpers Ferry inspires us still, to argue about historical rights and wrongs, to

to think about the clash of ideas and the cost of freedom. I’m hoping someday it will even inspire the leaders of Marlborough to give back the stolen bell.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo